'10,000-year fest' conjures Ainu wisdom of ages

Photos and story by Tetsuo Nakahara - Published on Stripes Japan

The scared rice wine was poured onto the “inau,” a ritual stick topped with wood shavings, as a group of Ainu people sat around the fire praying to the Great Spirit. The ceremony is called “Kamuinomi.” I was witnessing a form of worship practiced hundreds of years before Ezo, or the Land of Ainu, ever became Japan’s northern most prefecture of Hokkaido.

I had this opportunity during my recent journey to the far north. I wasn’t sure where my quest would take me next, but for those few days (Aug. 11-17) the Ainu Moshir Festival in Biratori, Hokkaido was definitely the place to be.

The festival, also known as the 10,000 Years Festival, has taken place every summer for 25 years. More than 800 people come from all over the world annually, with tents and sleeping bags in tow, for a week-long camp-out in Hokkaido’s wilderness to celebrate Ainu culture and glean from some of their traditional ways.

The Ainu are the indigenous people of northern Japan. Their name literally means “human” in the Ainu language. Ainu tradition espouses a deep reverence for nature and the belief that gods exist in all natural things. According to this animistic belief, each entity comes from its own world and returns to it after accomplishing its role on Earth. Today, the lifestyle these beliefs promote garners attention from around the world for the ecological wisdom it embodies.

The Ainu Moshir, or Great Land of the Humans, Festival features Ainu dance performances, workshops and live music. It also attracts a 60s-era hippie contingent, prompting organizers to declare it a “drug-free” event. You have to rough it at this primitive mass campout, but it is a rare experience you will never find vacationing at a luxury hotel. Children play naked in the forest; people bath publically in the river.

A big fire pit was set in the center of the festival’s main field. The fire was kept lit for the entire week, to enable the traditional Ainu practice of offering prayers to the god of fire before any undertaking is carried out.

“Ten thousand years ago, there were no ‘Japanese,’ ‘Ainu’ or ‘foreigners.’ We were all the same – children of the Great Spirit. And the land was all shared,” explains Rera Asir, the Ainu Moshir organizer. “Humans have repeated the tragedy of killing and depriving one another throughout history. We need to go back to our roots.”

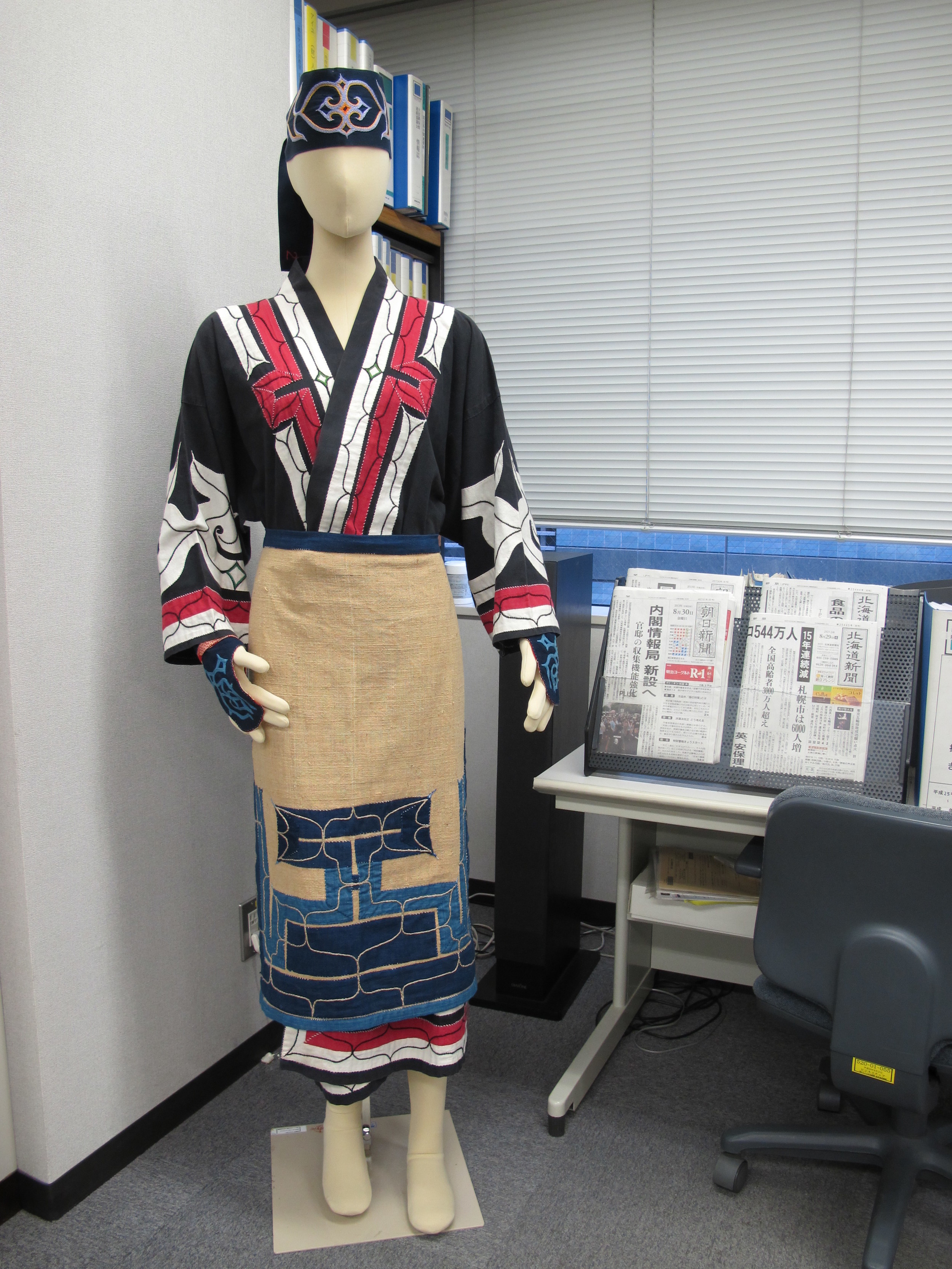

Traditional Ainu beliefs emphasize that life should never be taken unnecessarily. It also stresses an interaction between nature, humans and the gods in which natural materials in ones surroundings are used respectfully for clothing, food and housing. To that end, the festival offered many workshops on traditional uses of natural resources such as dyeing cloth with indigenous plants, weaving textiles and the use of natural medicines.

“Today, the knowledge passed onto us from our ancestors may be needed in times of disaster,” says Asir. “It is important to remember this wisdom and pass it on to the next generation.”

Taking this advice to heart, I also visited Nibutani Ainu Cultural Museum in Biratori, which is near the festival site. Nibutani is a well-known sacred place for many Ainu, and has the densest population of Ainu in all of Hokkaido. The museum houses more than 10,000 cultural artifacts, including Ainu clothing, toys and hunting implements.

It was amazing to see so many rare items such as shoes made of salmon skin and water bags made from animal bladders. There were also many inau and other ritual implements, including those once used for the “Iyomante” ceremony to send off the spirit of a bear after it was hunted. The center is well organized and informative.

Outside the museum there are also some traditional Ainu houses on display where you can actually go inside and see how these people once lived. There is also an hour-long movie in English that you can watch, as well as English-language books about the Ainu on sale.

At the end of the festival, I was still unsure where to continue my quest in the Hokkaido wilderness, so I asked Asir for suggestions.

“Go to the east,” she said. “We Ainu moved toward the east because that is where the Great Spirit is. So, go east.”

I followed her advice and had a great time camping and communing with nature.

The plight of Japan's native northerners

Ainu people are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaido and northern Honshu as well as the Kurile Islands and the southern half of Sakhalin Island. About 150 years ago, they hunted bear and deer, spearfished for salmon, worshipped nature and tattooed their young women’s lips as a rite of passage.

Today, it may be hard to distinguish the lifestyle and culture of many Ainu from the rest of Japan’s people. Many can no longer speak Ainu fluently, and much of their traditional ways have been relegated to an occasional ceremony or cultural festival.

Ainu culture may date as far back as the 13th century. Since they did not have a written language, but instead used “yukar,”or poems, to pass history and tradition from one generation to the next, much of their past is unknown. What is known is that the land they once lived on was called Ezo, and they were fishers as well as hunter-gatherers that whaled and caught sea lions and swordfish on the open seas until they were driven inland by encroaching Japanese.

For centuries, the Japanese and Ainu lived in peace. The Ainu traded furs for sake, pottery and hunting tools with the Japanese as well as the Chinese, Tungus (a Siberian tribe) and Russians. As Russia and Japan expanded, however, so did their interests in Ainu territory, eventually sealing the fate of these aboriginal people. Three major Ainu-Japanese wars between 1457 and 1789 drove the Ainu northward.

After Japan’s Meiji government was established in 1868, it annexed Ezo, renamed it Hokkaido and Japanese pioneers flocked to the new frontier. In what should be a familiar scenario to most Americans, Ainu land was redistributed to Japanese farmers. Ainu language and customs were banned, and their children put into Japanese schools. Government assimilation policies were followed by isolation, poverty, lack of education and discrimination from Hokkaido’s new majority.

It wasn’t until the 1960s, when younger Ainu where inspired by national and international civil and human rights movements, that the Ainu began to gain greater access to opportunity in Japan. It wasn’t until 2008 that Tokyo acknowledged the Ainu as “an indigenous people with a distinct language, religion and culture” (thereby closing Japan’s oft-used loophole that there can be no discrimination because there is no minority).

Today, there are about 23,782 Ainu in Hokkaido, according to the prefectural government there. Most are mixed Japanese. But over the decades many Ainu have migrated throughout Japan, especially to large urban areas, in search of greater opportunity and, in some cases, less discrimination. More than 5,000 Ainu live in Tokyo, according to Ainu Cultural Center, Tokyo.

“I was born in Hokkaido, and we moved to Tokyo when I was 4,” said Hitomi Kihara, a staff member at the cultural center. She added that her mother is Ainu and her father is Japanese. “I hear some people still suffer discrimination, especially in Hokkaido. But I was treated like everyone else growing up in Tokyo. … However, I did feel like I had to tell my husband (that I am Ainu) when we started dating, because some people still have strong prejudices against Ainu.”

Although Ainu culture is now officially recognized, a longstanding economic gap between this minority and its Japanese counterpart still exists today. Discrimination can still be found sometimes in schools, workplaces and marriage considerations.

Music in Ainu tradition

Early Ainu music was associated with festival singing and dancing, and was related to spirit deities called “Kamui” and animals such as bears, whales, owls and sea turtles. Musical instruments were used for telling epics stories, praying, greeting, magic spells or just for entertainment.

Many songs are accompanied by hand-clapping alone, or the singers form a circle or perform a pantomimic dance in Ainu culture. The five-string “tonkori” and “mukkuri”, a bamboo jaw harp, are the most popular Ainu instruments. Animal cries and natural sounds are improvised with mukkuri.

Honoring the sacred bear

The Ainu had great reverence for bears. Bears were providers of food, fur and bone for tools. They hunted them, kept them as pets, and performed exorcisms involving bear spirits. Sometimes bear cubs were caught and nursed by women. The bear was regarded as an important mountain god in disguise.

The most important Ainu rite was the “iyomante.” Conducted in the spring, it was essentially a funeral to give the bear and mountain god spirit a proper send off before it returned to the mountains. A female bear and her cubs were caught. The bear was killed and her spirit was sent to the gods in a special ceremony. Her cubs were then raised by the Ainu for several years and they too were returned to the gods.

Ainu timeline through history

1400s: The Ainu’s first contact with Wajin (Japanese) and the start of peaceful trading.

1457: The Battle of Kosyamain: Sparked by the fatal stabbing of an Ainu boy by Wajin merchants in Hakodate, the year-long war lead to the destruction 10 out of 12 Japanese settlements and the near expulsion of all Japanese. A century of intermittent warfare followed.

1669: The Battle of Syaksyain: The Ainu leader Shakushain led a large force against Japanese merchant operations and settlements, killing 200-400. Using firearms, Japan’s Matsumae Clan suppressed the rebellion. Shakushain was assassinated during peace negotiations.

1789: The Battle of Kunashiri-Menasi: Seventy-one Japanese were killed in an uprising. It was suppressed by the Matsumae Clan aided by a local Ainu leader. Thirty-seven Ainu were executed afterward. The Matsumae Clan began to rule over the Ainu.

1869: Japan’s government officially claimed Ezo and renamed it Hokkaido; a mass migration of Japanese ensued.

1871: Traditional Ainu lifestyle outlawed: Forced use of Japanese language, homes burned and families relocated upon the death of a family member, traditional tattoos and earrings banned.

1878: Colonization Commission applies the administrative name “Former Aborigines” to the Ainu.

1889: Deer hunting prohibited.

1899: The Hokkaido Aborigine Protection Act: Ainu encouraged to abandon traditional hunting and fishing lifestyle and become farmers, and conscripted as labor to develop Hokkaido.

1960-1970s: Influenced by worldwide civil and human rights movements, the Ainu begin their struggle to affirm cultural identity and counter discrimination.

1992: Ainu representatives first testify before UN Committee on Indigenous Rights.

1994: Shigeru Kayano becomes first Ainu elected to the Japanese parliament’s Upper House.

1997: Act on the Encouragement of Ainu Culture and the Diffusion and Enlightenment of Knowledge on Ainu Tradition passed: Emphasises supporting Ainu culture, but falls short of addressing human rights issues.

2008: The Japanese parliament unanimously adopts Resolution Calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People. The Advisory Panel of Eminent Persons on Policies for the Ainu People is established to come up with a “comprehensive” Ainu policy.

- See more at: http://okinawa.stripes.com/news/northern-exposure#sthash.qAXTuEUK.dpuf